Predictions of Longevity within the Smoking Population of the United States

12 Aug 2013

Reading time ~5 minutes

Mortality Rates

of smokers have been studied in many counties in order to understand external influences and effects of population demographics [i][ii][iii]. An article by P. Jha et al. in the New England Journal of Medicine analyzed hazards of smoking while adjusting for variables of education, alcohol consumption, and adiposity within the population of the United States. The findings in the article were unique because it looked at mortality of individuals that have quit smoking.

We assessed the hazard model that was used in the article and found that improvements can be made in covariates of education, adiposity and levels of alcohol consumption. Since the study considers the population of those that have quit smoking, it would be appropriate to study the quality of life and whether it had an influence on cessation.

We did not use the income variable as there was a tendency for bias within the lower income brackets[iv]. Pre-analysis indicates that there are higher rates of missing income information within groups that relies on welfare support and food stamps. A substitution with a variable that indicates the usage of welfare and food stamps can be used to measure the quality of life. Covariates of education was stratified as we do not expect linear relations with mortality. The knowledge of the health risks in smoking is different in elementary school, secondary School, and post-secondary education.

Modelling with adiposity variable, BMI, requires a more complicated approach to account for the non-linear relation with health[v]. Recent studies have shown that slightly overweight individuals may have an advantage over underweight individuals[vi].The relation between BMI and smoking status are also ambiguous since smoking status have been shown to influence BMI[vii].

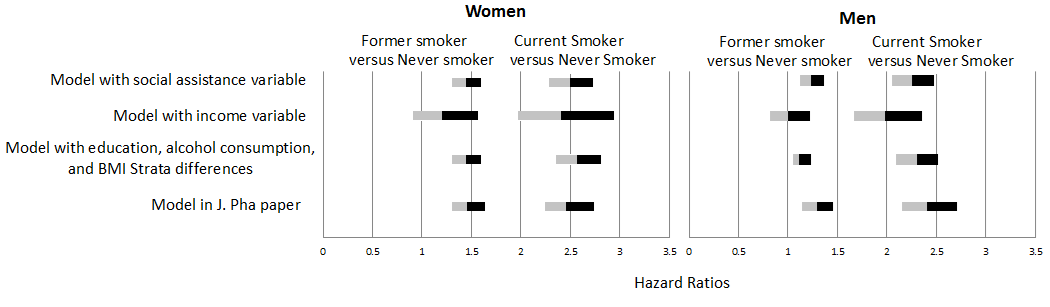

When determining the hazard ratios for current smokers and former smokers against non-smokers, we discovered that confidence intervals were reduced with stratification of BMI and education variables (figure 1). We saw further reduction and improvements when the variable for social status was incorporated.

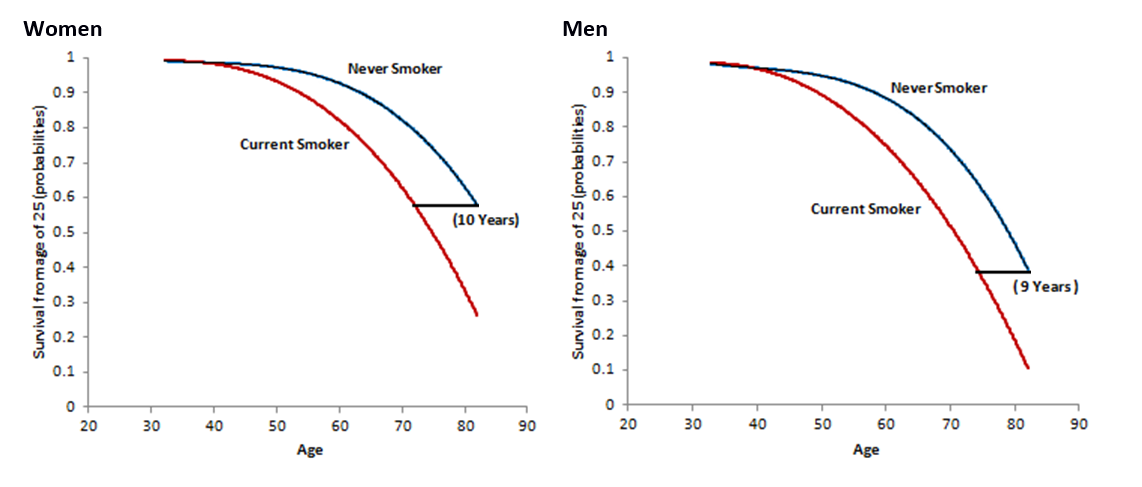

A crude way of estimating the probability of survival for current smokers compared to non-smokers was used, which helped us understand the reduction in longevity due to smoking. The results of our model gives hazards ratio and probabilities but to transform probabilities into years reduced after cessation required a revised model(Figure 2). It was determined that in general, smoking will result in a reduction of 10 years for females and 9 years for males, compared to 11 years for females and 12 years for males in original study.

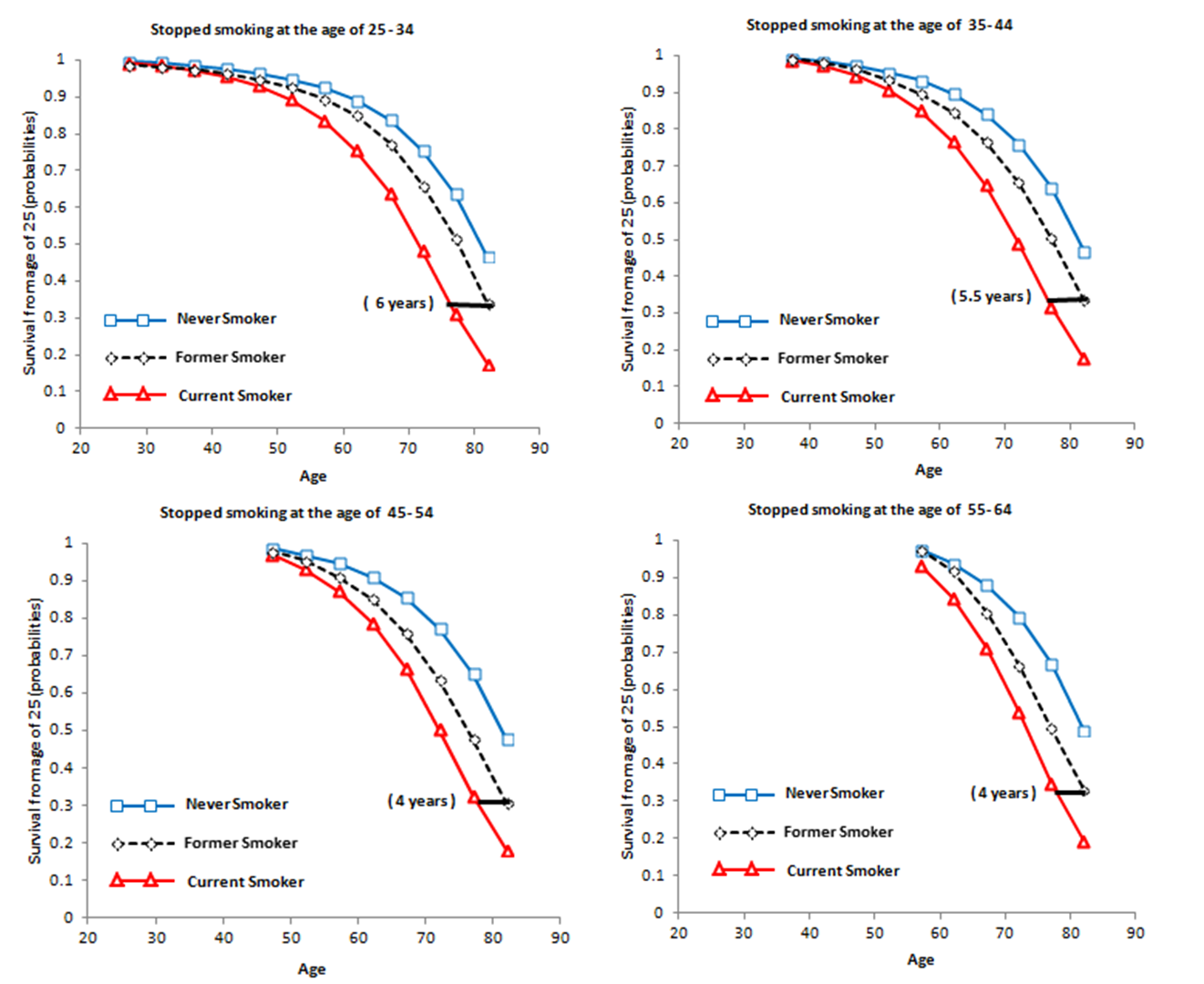

with a large data size, the results on benefits of cessation from subcategorizing the age when cessation happened is reliable. It is evident that the earlier a smoker quits, the better the health will be in later years, thus an important factor in achieving a more meaningful outcome is to analysis whether the benefits are time bounded.

Using the same technique to determine the reduction in longevity, we determine the years gained by a successful cessation, by analyzing the difference in the probability curves of former smokers compared with never smokers. Analyzing the years gained within each age bucket of cessation, we found that quitting at the age of 40-50 had the most impact on health (figure 3). Our findings also show that those that quit smoking before the age of 25 has an almost identical mortality to those that have never smoked.

Although it is exciting that our findings show little impacts on health if we quit smoking before the age of 25, the analysis is based on past events. Society is constantly changing and at non-linear rates. The most that this study can offer is a historical summary of the population of United States and the results should be used with considerations.

Data was collected from the U.S. National Health Interview Survey between the years of 1997 and 2004[viii]. In the following years up until 2006, death records of interviewed individuals were collected from the National Death Index [ix]. Data Analysis was done using SAS and Stata software with similar adjustments to the P. Jha paper.

Acknowledgment

All support and assistance from Professor Paul Grootendorst is greatly acknowledged, an additional acknowledgement goes to Professor Alison Gibbs and the SAS company for the free subscription to the statistical program SAS.

Reference

i)Jha P, Landsman V, et al. 21st-Century Hazard of Smoking and Benefits of Cessation in the United Stata.N Engl J Med 2008; 4:341-250.

ii)Basavaraj S. Smoking and loss of Longevity in Canada. Canadian J of Public Heath-Revue 1993;3:341-345.

iii)Pirie K, Peto R, et al. The 21st-Century Hazard of Smoking and Benefits of Stopping: A prospective study of one million women in the UK.LANCET 2013; 9861:133-141.

iv)Turrell G. Income non-reporting: implications for health inequalities research. J Epidemiology and Community Health 2000;54:207-214.

v)De Gonzales AB, et al.Body-Mass Index and Mortality among 1.46 Million White Adults. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:2211-2219.

vi)Curtis JP, et al. The Obesity paradox – Body mass index and outcomes in patients with heart failure. Archives of Internal Med 2005;165:55-61.

vii)Sneve M, Jorde R. Cross-sectional study on the relationship between Body mass index and smoking, and longitudinal changes in body mass index in relation to change in smoking status: The Tromso Study. Scandinavian J of Pub Health 2008; 36:397-407.

viii)National Health Interview Survey. Hyattville, MD; National Center for Health Statistis, May 2013 (http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis.htm).

ix)National Health Interview Survey (1986-2004) Linked Mortality Files, mortality follow-up through 2006: matching methodology. Hyattville, MD: National Center for Health Statistic, May 2013 (http://www.cdc.gov/nhis/data/datalinkage/matching_methdology_nhis_final.pdf).